Conceptualizing the UN Sustainable Development Goals

Opinion: Georgina Mace, Professor of Biodiversity and Ecosystems and Director, UCL Centre for Biodiversity and Environment Research

We set out to consider how the SDGs could be organized so that potential synergies among them could be realized (“finding the win-wins”) , but also to recognize the reality that there are clearly conflicts too, and that these need to be identified and carefully managed so as not to undermine the broader objectives (“dealing with the trade-offs”).

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) represent a significant shift in focus. Unlike their predecessors, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which were concerned with measurable outcomes relating to the health, income and wellbeing of people, the SDGs also include the life-support systems (food, climate, energy, water etc.) and other aspects of the built and natural environment. From the perspective of a natural scientist, it makes perfect sense that the environmental systems that support people are included in the goals, and not just the health and welfare outcomes. But the breadth of goals, and the vast number of interests and organizations involved, does pose some risks. The 17-goal proposal has led to some doubt as to whether such a broad approach is sensible. The range of organizations and activities involved can make the task appear overwhelming, with many questions concerning achievability, governance and accountability. So, how can the goals be organized and aligned to make the task achievable?

My colleagues and I in London set out to consider this problem. The group was an interdisciplinary one, led by Professor Jeff Waage of the London International Development Centre, involving academic researchers from University College London, the School of Oriental and African Studies, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the Royal Veterinary College. The group has experience across sectors, in development, engineering, child and public health, ecology, wild animal health and public policy, legal and governance systems. We considered how the SDGs could be organized so that potential synergies among them could be realized (“finding the win-wins”), but also to recognize the reality that there are clearly conflicts too, and that these need to be identified and carefully managed so as not to undermine the broader objectives (“dealing with the trade-offs”).

Like any interdisciplinary group, we struggled with differences in terminological and conceptual understanding. Apart from the semantic differences among such a broad group, the varying approaches to even posing and then going about answering questions were significant. Some areas were easier to address than others. Interestingly, it turned out to be rather straightforward for the sub-group working with education, public health and gender issues to find the win-wins. Enhanced public health and education, education of girls, eliminating poverty and striving for more inclusive and equitable societies all present a coherent body of public policy, drawing on a strong evidence base, that suggests the synergies and win-wins are both real and achievable. In addition, these programmes are the core business of local and national governments, and they are already fairly well embedded in society. However, for other areas the working groups struggled with aligning the goals. In considering agriculture, biodiversity, climate, water and energy, for example, there were a few win-wins but many trade-offs. The winners and losers were often linked to certain goals meaning that meeting one would make meeting others more difficult. More generally, we found no means to align governance or desirable outcomes in helpful ways. There seemed to be several goals with different winners and losers, and very diverse arrangements for responsibility and accountability, widely distributed across nation-states, local government and corporations, and involving national and international, public-sector and private-sector bodies.

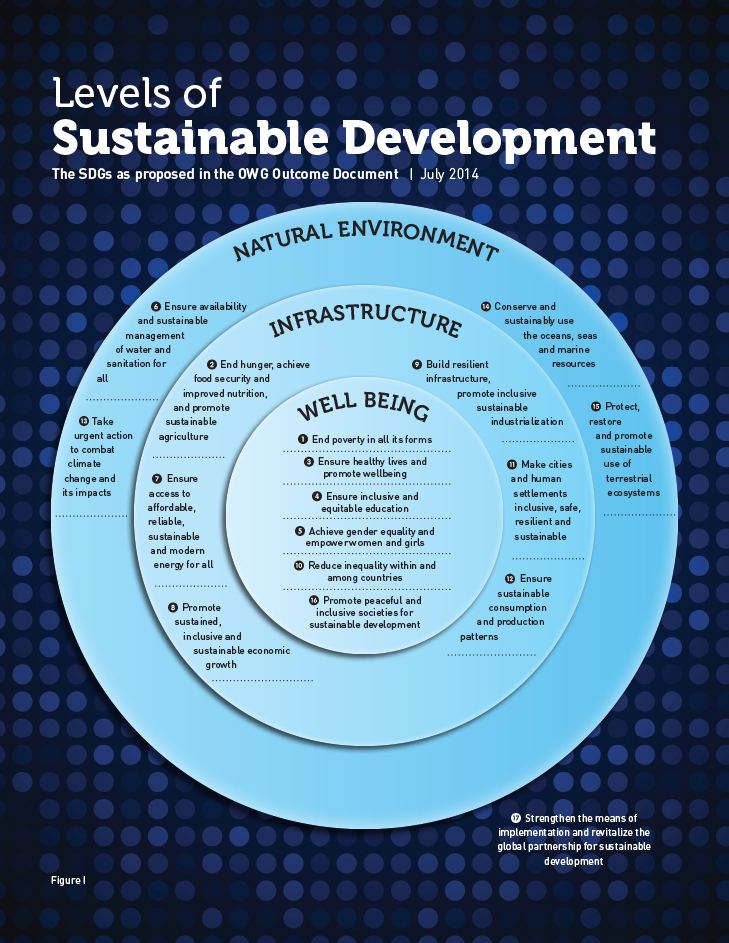

The reasons for this became apparent when we organized the goals into concentric layers, with the centre representing the health and wellbeing outcomes, and the outer ring being the natural environment. The middle ring includes all of the goals that support health and wellbeing, often drawing on resources in the natural environment (Figure 1).

The inner-level goals (“Well-being goals”) are people-centred goals for health, education and nutrition outcomes. They focus directly on welfare and its equitable distribution within and between individuals and countries. The middle level (“Infrastructure goals”) relates to various kinds of networks and mechanisms for the production, distribution, and delivery of goods and services including food, energy, clean water, and waste and sanitation services in cities and human settlements. These goals transcend individuals, households and communities, and address many of the perceived essential functions of modern society within and sometimes beyond nation-states. They are necessary platforms for achieving inner-level outcomes. The outer-level goals (“Natural environment”) relate to global resources and global public goods such as land, ocean, air, natural resources, biodiversity, and the climate system. Here are the biophysical systems that underpin sustainable development. While not dependent on human activities, these systems are strongly influenced by them. They typically require international and transnational cooperation for their realization. We found that the win-wins and trade-offs between SDGs, and resulting challenges for governance, emerge from this classification.

The inner-level goals (“Well-being goals”) are people-centred goals for health, education and nutrition outcomes. They focus directly on welfare and its equitable distribution within and between individuals and countries. The middle level (“Infrastructure goals”) relates to various kinds of networks and mechanisms for the production, distribution, and delivery of goods and services including food, energy, clean water, and waste and sanitation services in cities and human settlements. These goals transcend individuals, households and communities, and address many of the perceived essential functions of modern society within and sometimes beyond nation-states. They are necessary platforms for achieving inner-level outcomes. The outer-level goals (“Natural environment”) relate to global resources and global public goods such as land, ocean, air, natural resources, biodiversity, and the climate system. Here are the biophysical systems that underpin sustainable development. While not dependent on human activities, these systems are strongly influenced by them. They typically require international and transnational cooperation for their realization. We found that the win-wins and trade-offs between SDGs, and resulting challenges for governance, emerge from this classification.

“Well-being goals” have similar governance and institutional structures, traceable to the role of the state in relation to the provision of health, education, and welfare and broadly points to win-wins, such as the linking of education, health and gender goals around opportunities to improve sexual and reproductive health objectives. There are, of course, challenges in achieving the well-being goals, for example overcoming historic differences and transforming social norms, especially related to gender inequalities. Even where relevant institutional structures and delivery mechanisms exist, many developing countries will require continued support to strengthen structures and institutions for the inner-level goals in order to govern effectively.

“Infrastructure goals”, in the middle ring, represents a new focus on global development goal setting, and bring particular challenges stemming from their relations with both the “well-being” and the “natural environment” goals. On the one hand, by improving access to water, food and energy, and by supporting economic growth, these goals help to achieve “well-being goals”, and this feeds back positively on “infrastructure goals” through, for instance, a healthy and educated labour force. But very importantly, the “infrastructure goals” are also designed to determine the way in which human societies use environmental resources and services to improve their well-being. ‘Sustainability’, a component of several goals at this level, is linked to how these environmental services are used. This central, mediating position means that these infrastructure goals are confronted with multiple demands which are often in conflict. For example, there are often competing demands for land use (for food, urban infrastructure or energy), or conflicts arise as the by-products of one activity compromise another (e.g. energy versus climate; food production versus environmental conservation). In addition, there are particular governance problems relating to conflicts and trade-offs with multiple stakeholders, made worse by the fact that it is here that much of the global economy is concentrated, and where decisions are typically taken by a small number of powerful public and private actors, by elites, and by technical experts on behalf of the wider public.

“Natural environment goals”, relating to reducing climate change and safeguarding marine and terrestrial ecosystems, natural resources and water supplies, are closely interrelated with one another, and there are potential win-wins such as the effect that forest conservation may have on tackling climate change. This level has currently the most fragmented governance and institutional landscape, often involving non-binding international agreements and conventions (e.g. UN Convention on Biological Diversity and UN Framework Convention on Climate Change). Governance structures focus on monitoring and convening processes and are not clearly linked to “well-being goals” and outcomes. Incentives for stronger governance at this level are weak, as they rely on greater levels of cooperation and investment in sectors in which the outputs/rewards are less apparent to the voters in any single country and may be inter-generational. The current approach of attempting to govern “natural environment goals” separately from “infrastructural goals” has meant that the burden being placed on global governance initiatives is too great. Addressing environmental sustainability at the level of “infrastructure goals” seems a more promising approach.

For these reasons our conclusion is that good governance of goals in the middle level (“Infrastructure goals”) is a priority. Given the crucial role played by institutions at this level both underpinning the outcomes in the inner (“Well-being”) level, and in driving environmental conditions (Natural Environment”) in the outer ring, decisions ought not to be taken by an unaccountable few. If the significance of the “infrastructure goals” is recognized then we think the prospects for achieving the SDGs will be greatly improved. A broad-based consensus derived from legitimate political procedures of all concerned parties will be vital for the viability of the SDGs agenda.

This paper was produced as part of the London International Development Centre – University College London collaborative research project, Thinking Beyond Sectors for Sustainable Development, funded by UCL Grand Challenges. The work is published as Waage, J., Yap, C., Bell, S., Levy, C., Mace, G., Pegram, T., Unterhalter, E., Dasandi, N., Hudson, D. &Kock, R. (2015) Governing the UN Sustainable Development Goals: interactions, infrastructures, and institutions. The Lancet Global Health, 3, e251-e252.

Georgina Mace is Professor of Biodiversity and Ecosystems and Director of the UCL Centre for Biodiversity and Environment Research (CBER)(http://www.ucl.ac.uk/cber). Her research interests are in measuring the trends and consequences of biodiversity loss and ecosystem change. She has worked on IUCN’s Red List of threatened species, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, and the UK National Ecosystem Assessment and is currently a member of the UK Government Natural Capital Committee.

Georgina Mace is Professor of Biodiversity and Ecosystems and Director of the UCL Centre for Biodiversity and Environment Research (CBER)(http://www.ucl.ac.uk/cber). Her research interests are in measuring the trends and consequences of biodiversity loss and ecosystem change. She has worked on IUCN’s Red List of threatened species, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, and the UK National Ecosystem Assessment and is currently a member of the UK Government Natural Capital Committee.